I am in Rabat Ville. The white taxis, not the blue petit taxis, act as buses. They take you and 5 other people from one stop to another. If you want to get out along the way, you can. You and 5 other people, in a small compact car with, of course, a driver. Two passengers in the front, and four in the back. The cost is 5 dirham each. As a woman, they place you next to women when possible. Groups of women, and groups of men. You would never be placed in the back – woman man woman. Yet, when 6 people are crammed in a small car, of course you may or may not be sitting on top of a stranger. It amazes me, no amuses me, in this instance, that they consider their rules sound. However the first time I sat next to a man in a white taxi, I was not amused. Full robe, long beard, mid 30’s. His leg continued to flex as I sat on him. His legs continued to spread wider, and he continued to give me less and less room. And more times than absolutely necessary, his hands were touching me. This is the time I was groped in the taxi.

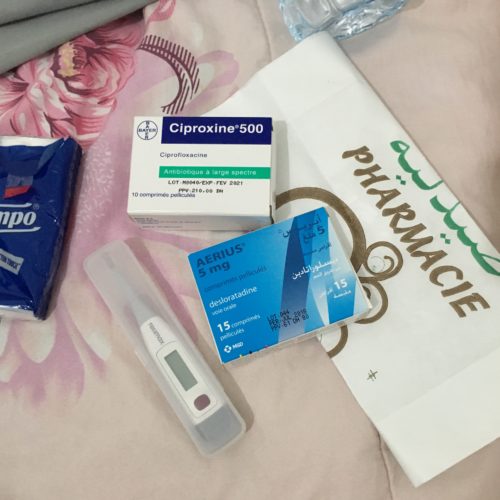

I am sick. Possibly very sick. I just arrived in Rabat after a long trip from Paris and after spending the night in the Casa airport. Three days prior, I received an antibiotic from my doctor over the phone. However, she insisted that if I developed a fever, I must be seen. The Casa airport was freezing. I was tired, yet didn’t sleep at all, because I shook from my fever. Now, I am in Rabat. Maybe the airport was just cold, or maybe, I now have a kidney infection. My back hurts, but it’s not sore and it’s just on one side. My nose is dripping, and I am extremely sick. One more day. I wait, I hurt, I wait. I research doctors, embarrassed to ask my host just how I’m going to get a prescription in Morocco. In fact, I can’t. They don’t speak English or French. I research— this is what will happen to me if I don’t get antibiotics, this is how I might call a doctor, and this is my plan. I will go to the pharmacy, and ask them for a thermometer and antibiotics. I search for 15 minutes before class in the morning. I leave the medina, and make it to the new city. I find a pharmacy. They speak French. I show her my prescription bottle and tell her I finished it and it’s not working. Now, my back hurts and I need this other kind. Sure enough, they have that. It’s in a white box, like everything else, with the name of the drug. No confusing or fancy packaging, no suggested uses. What else to I need? I get my thermometer, and 15 allergy pills for the cats. 300 dirhams. This is the time I thought I might die but lived in Morocco.

I am late to meet my friends for our afternoon trip to Salé. I just got out of school and off the taxi. I’m walking along the beach, which is the long way, but I don’t know the medina well enough. It’s windy. It’s so windy, and the waves are crashing above the rocks. I come to the cove of the cliffs. There’s a large crowd of people. Ambulances, police, and rescue divers. I approach to see the divers on a ledge just below the cliff. I take a photo with my phone. They have ropes going down into the water. I am late to meet my friends. I find a man who may speak French. “What happened?” I ask. There are two children in the water. “Two children, are you sure? This is the second time this week,” I said. I understand that two men got swept into the waves and onto the rocks last week. He tells me they’ve been looking for three hours. The crowd gets louder and louder. I don’t speak Arabic, but I know what they’re saying. “Back up! Are you crazy, the waves are too high right now. Can’t you see what happens when you get too close? Don’t you have any respect?” I ask the man, “The parents, are they here?!” He responds, “Yes, the boys are from two families. They’ve been here praying.” I cry. I am so sad. The yelling gets louder. They are here next to me, the mothers of these two boys. They push everyone back. They join hands and push. Creating a boundary for which people must respect their loss. And what loss! They push and push. They have white cloths they make into ropes and push and cry out. I can’t stay. I am crying and I had no respect for taking a photo. I pray that I understood him wrong. I pray that these are the same two children from this week—and they are. Earlier this morning, they found one of the boys not far. And now they search for the other boy. I turn to walk away up the street along the beach. The cemetery that I once loved so much rises across the entire hillside into the city. This is the day I understand loss.

I leave the house with my roommate. We are going to Hassan Tower with another friend. We get to the street. There is lots of dancing and drums. So many flags. Did I hear the king of Jordan was in town? Moroccan flags are replaced with flags of Jordan, and Moroccan flags fly high in peoples’ hands. We talk and talk and talk with people on the street. The king of Morocco is coming home. Should we stay? Of course we should. We meet crowds of people from Senegal. I take photos, and video. I learn that Senegalese don’t mind photos, but that Moroccans do. I dance, in the middle of an African drum circle. Hours pass. Is the king really coming? We walk to find water. We find people we know. We find the main avenue where the barricades are set up for a parade. Ok, the king is coming. We find water. We wait more. And now, people are not allowed to cross the street. A police car with a siren passes. One minute more, and another passes. Ok, the king is here. Black car after black car, with armed guards in the sunroof pass. And there’s the king. Waving from the sunroof. The people are crazy. Crazy happy to be Moroccan. Crazy happy to see the king. He passes, and he is gone. Now, four hours later, we will go to Hassan Tower. This is the day, I saw the king of Morocco.

Today is Wednesday. This morning, we were told the girls in the family would be going to hamman between 16:00 and 17:00. We were invited to go. “Hamman, good.” Now, what I’ve heard about hamman so far is only since I arrived in Morocco. It’s a public bathhouse where everyone is in the same room and scrubs each other. I was also told that it was a wonderful experience, and of course, when in Morocco… So we wait around, and by 17:30, the women are ready. This is apparently the event of the week, because we are rolling buckets and buckets and duffel bags down the street. We arrive and are greeted by the naked women who work there. We change out of our clothes and open a big heavy door to the bath. There are two rooms. No one is in the first, so we walk through to the second. At this point, I can’t see anything, as my glasses are on my head and there’s quite a bit of steam. It’s hot. Someone takes my shoes and my glasses. I obviously don’t know what I’m doing. A bunch of brown stuff suddenly comes flowing down the middle of the room. Eww. Is that dirt? No, it’s henna. We sit on mats on the floor. The workers fill our buckets with hot water. And we begin to scrub. Henna first, then some other, smoother salve. We do this for a very long time. Sadhia orders us our ‘massage’ and shower. Turns out, our massage is what everyone else is doing to each other, their loved ones. Our ‘massage’ is the attendant giving us an exfoliating treatment by scrubbing our bodies as hard as possible. Oww. I’m sure this works, because it hurts too much not to. She scrubs and scrubs and scrubs. Again, this goes on for a long time. Then, a bucket of water is on my head. Hamman, goooood. Then, I go back and wait some more. Now, my skin is so smooth, I don’t know what to do with the rest of my time. Wait, she’s back. Now, she has me sit on a bucket. She washes my hair. Brushes my hair. Now that is all. It’s very hot in here, and we’ve been here over an hour. I go sit in the first room. It’s cooler, and cleaner. I rinse and rinse more. Finally, we are ready to leave. I gather my shoes, my clothes, my glasses. My body has never been this clean or my skin this smooth. As the family gets out and finds their robes, the grandma approaches. She gives me kisses. Kisses on the cheek that I have yet to receive in Morocco. One, two three kisses. Then, from Hazma, then, from Sadhia. This is it. This is the event that brings you close enough with the woman around you. This is when I went to hamman with my family.

I get to my riad in Fés. It was particularly easy navigating a new town, by myself, with my knowledge of Rabat under my belt. “Aleah, hmmm.” He enters my name in his inbox on the computer. Nothing comes up. I show him the screenshot with my reservation number. No, it’s not there. I log into wifi, open my e-mails and the app. Show him once more. “You are not here, no problem,” he says. “I’m sorry, but maybe you will leave your bag here, and when you return, we will have your bedroom ready across the street. There are no rooms here. Mashi mushkil. Pas de problem. No problem. I come back at 18:00. “You want your room now?” Yes, please. An old woman comes to the door to take me across the street. She reminds me of my host grandmother, except she speaks French. We go inside her riad. It is beautiful. More beautiful than the one I was supposed to stay in. It looked like one of the madrasas I just paid to see in the medina. My room is full of furniture, and they start to clear it out. Mashi mushkil. Pas de problem. No problem, I say. She keeps working. I change my shoes, use the bathroom and leave once more for tea. When I come back, my room is clean. The key to my room is an art form, and opens a tiny door in a much larger door. There is blue tile everywhere, and I’m the only one staying in the building. Of course, I was not to be upset when the first place didn’t have my reservation. This is Morocco. This is when I checked into my riad in Fés.

I am in the medina of Fés. I have just entered through bab bou jeloud, the blue gate. There’s a map in my hand that the concierge gave me. A blue pen circled the route I should take through the medina. Each attraction is circled on that route. Nejjarine, Quaraouiyine, Chouara Tannery, etc. Where is Nejjarine? The street is busy, very busy, with open shops along both sides and tons of tourists. But it doesn’t feel like I’m on the same street I started on. So I ask to make sure I’m going the right way. “Oh that? It’s that way,” he points. He’s not leading me, so I believe him. I soon realize that I’m no longer near people, I look back, and he’s now following me. “Oh, I’m lost?” He says. Let him help me. Ok, no. I’ve learned my lesson— apparently they are trickier than I thought. I keep walking. Nejjarine, Quaraouiyine. I only fall for this one more time. Then the crowds thin out. The shops aren’t as often, but I’m sure I’m on the right track. I’m looking for the tannery. I refuse help from everyone saying “Tannery?” Because I know I will have to pay them. I keep walking. I get scared. And I begin asking the older trustworthy-looking shopkeepers, women, and children. I can’t find it. I believe maybe some of these people are showing me the right way, but there are no tourists around. Isn’t the tannery a main attraction in Fés? Why are there no people? I ask again. This time, I ask the wrong person. He smiles, of course, he can show me where the tannery is. Oh, las, choukran, no thank you. No but really. Then, another man, noticing my annoyance with the first, says, “Tannery? I can show you.” Las, choukran, no, no thank you. Soon, I realize I am surrounded by men, all offering to take me there. They insist, they will help me. “I can show you.” Las, las, chokuran. I am suffocating. I honestly can’t read their emotion or genuity. This is a first. I am scared. I have to stop myself from crying. Las, las las, chokuran. Why I’m still saying thank you is beyond me, but it’s one of the few words in Arabic I know. I turn back and run to where I last left people. It’s far. I get there, and think I’m giving up on the tannery. I find three teenage boys and no one else is around. I ask. Aafek. Please. Where is it? He motions, come. He takes me there, no cost. The door says Chouara Tannery. I still don’t believe it. The men at the door say yes, yes. Finally, someone helps me in. He of course is a guide, with that special card that basically says con artist. “See, I work here, because I’m wearing these boots.” He takes me down into the tannery. I feel special. I’ve only seen photos from the terrace. We walk around. He says come, you can take pictures from the terrace, too. He’s rushing me. But runs me up and down and up and down the stairs to take photos. He asks the workers, can I take photos of them? Yes. We do this a bit longer. Then we’re on the terrace. He says, “You need to pay him for me.” What? I mean, I’m not surprised, and I knew he would be the only person today that I had to pay for these terrible guide services. Ok, I pay him 10 dirhams. We run around more. Now, another person, you have to pay him for me. Ok, definitely no. I say no, I will pay you, when you take me to the door. Ok? Ok. He keeps walking, we’re not at the door, and he asks for money. I say no, keep going, I’ll pay you when I’m out. Ok, we get to the door. He insists, 20 dirhams. Ok, I don’t care. I’m out and I’m leaving. This is BS. This is the time I was scared in Morocco.